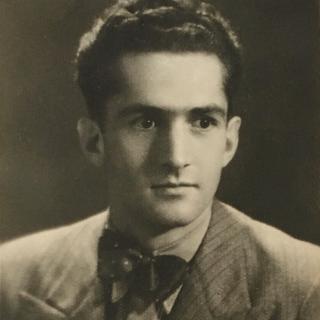

Richard Heider was born on 19 August 1912 in Zurich. He was living in Alexandria, Egypt, during the Second World War, when he was asked by the ICRC in early 1942 to carry out a one-off assignment: would he be willing to accompany a ship scheduled to sail from Egypt to Greece carrying urgent food supplies? Greece was occupied by Germany and Italy at the time, and the ship’s passage required the presence of an onboard convoy agent from Switzerland, a neutral country. That assignment, if he accepted it, would take him away from his job at the Helvetia cotton factory – and from his wife of three years – for a few weeks.

The initial plan was for Richard to sail on the Radmanso, a steamer that would deliver 7,000 tonnes of wheat from Egypt to Piraeus, Greece. In the end, that ship did not require a Swiss convoy agent and made the trip in March. Another ICRC shipment from Egypt to Greece was scheduled for late May using the Stureborg, a Swedish-flagged steamer, to transport around 2,000 more tonnes of wheat. In early April, it was thought that the Stureborg would not require a Swiss representative on board, and that it would not bear any Red Cross markings. To guarantee safe conduct, however, the Italian consulate insisted that the ship show the red cross emblem, while the German consulate required both the emblem and the presence of a Swiss representative on board.

The ICRC accepted these terms, and Richard agreed to serve as the convoy agent. His specific tasks included confirming that the physical cargo corresponded to what was listed in the bill of lading, and applying certain security measures. The departure date was nearly postponed owing to questions raised by the warring parties about the ship’s planned route. But on 20 May Richard travelled to Haifa, and the Stureborg set sail from that port at 6 o’clock in the morning on 22 May. The Swedish steamer reached Piraeus on 28 May. Because of the occupation, Richard was required to remain onboard, but he could not help but marvel at the happy crowd awaiting the Stureborg’s arrival.

While docked in Piraeus, Richard wrote to his father. In his letter, which he finished shortly before the Stureborg departed for Haifa, he noted that an ICRC delegate in Piraeus had asked if he would be willing to stay on in Greece to work for the ICRC. It is not known what he thought of that prospect but, in bidding his colleagues goodbye as the ship readied for departure, he announced with youthful enthusiasm: “We’ll be back in a month!”

The Stureborg left Piraeus on 5 June, with 21 people on board and the Red Cross markings still clearly displayed on the steamer’s sides and deck. For four days, the steamer ploughed ahead, with the ship’s wireless operator reporting its position three times daily to Athens. On the morning of 9 June, two Italian Caproni warplanes appeared in the sky and approached the ship. The ship’s crew signalled the vessel’s name and its connection with the Red Cross. The pilots disregarded that information and dropped torpedoes. One missed the mark but the other struck the Stureborg amidships, splitting it in half and sinking it almost immediately. At that moment, the steamer was only 27 hours’ sailing time away from Haifa.

Eleven of the crew members – including Richard, who was 29 years old – perished at once. The other ten salvaged a life raft and a sail from the wreckage, along with a small amount of food and water, and hunkered down. After drifting for 19 days, the life raft washed ashore near Gaza carrying a lone survivor. The other nine men had succumbed to both deprivation and the elements – scorching daytime heat and bone-chilling nights.

Richard’s willingness to take a chance, to put his life on hold, and to contribute however he could to the general good, is a notable example of the spirit of humanity that thrives during times of trouble and conflict.