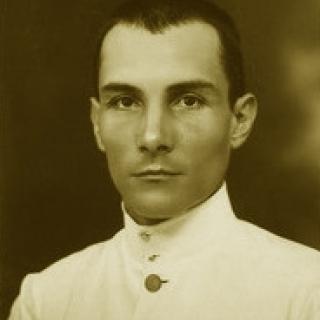

Matthäus Vischer was born on 29 August 1896 in Basel, Switzerland. He studied medicine in Basel and Bern, and received his diploma in 1922. After completing postgraduate internships at the Pathology and Anatomy Institute and the gynaecology clinic in Basel, he did an internship at the hospital in nearby Riehen. In 1926, he was recruited by the Basel Mission to work as a missionary doctor in Borneo, which was then part of the Dutch East Indies (and whose territory is now shared by three countries: Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei). He was the first doctor to travel to Borneo on behalf of the mission and was accompanied by his wife Elisabeth, a trained nurse, and the couple’s two children – they would have three more children in South-East Asia. Before leaving Europe, Matthäus took a course in tropical medicine in Tübingen, Germany, and spent time in the Netherlands learning Dutch.

The Basel Mission had been active on Borneo since 1921, carrying out its work among the Dayak, a tribe of feared headhunters. Its missionaries travelled to remote villages in the jungle, bringing medical aid, setting up schools and proselytizing. Matthäus was put in charge of the mission’s various operations in the southern part of the island, including the hospitals in the city of Banjermasin and the town of Kuala Kapuas. As the liaison between the mission and the Dutch colonial government, Matthäus was a well-known and respected figure throughout the area.

The Vischers’ plans to return to Switzerland in 1940 so their five children could attend school there were derailed by the outbreak of the Second World War. The Japanese Imperial Army’s sweep across East Asia reached Borneo in December 1941, and Banjermasin was occupied in February 1942. That prompted Matthäus to send a telegram to the ICRC offering his services as a delegate. At the time it was a relatively common practice for the ICRC to call on Swiss people living in remote parts of the world to represent the organization when necessary. The ICRC quickly approved his request, although its early-March telegram did not get through until June. Indeed, communication mishaps were a repeat occurrence over the following three years.

Matthäus’s primary responsibility as a delegate was to do his best to ensure the health and safety of prisoners of war and other detainees held by the Japanese. And records indeed indicate that, after the Japanese occupied south Borneo and interned Dutch nationals in the region, both Matthäus and Elisabeth began visiting camp detainees in April 1942, providing them with food, clothes and money. The occupation authorities attempted to stop the visits – and to curtail the detainees’ contact with the outside world – in late May when they tightened the rules at the camp. But that did not deter the Vischers from continuing their visits.

Immediately after approving Matthäus’s request, the ICRC sought to inform the Japanese authorities of its three delegates active in the Dutch East Indies – Dr Vischer in Borneo, Dr K.E. Surbeck in Sumatra and Mr Weidmann in Batavia (Jakarta) – and to secure the authorities’ approval for their humanitarian activities. Receiving no reply, the ICRC reached out repeatedly to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs throughout the year. In November 1942 the ministry replied with a curt message to say that it was examining the question of the delegates’ status. More entreaties from Geneva followed, with another vague reply received in May 1943. Finally, in mid-August 1945, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs informed the ICRC delegate in Japan that it accepted the delegates proposed by the ICRC, including Dr Vischer. In all, the ICRC sought to contact the Japanese authorities 19 times between 1942 and 1945, receiving only four replies.

Unfortunately, Japan’s 1945 message was based on imprecise information. It turns out that Matthäus and Elisabeth had been arrested by the local Japanese military in May 1943, and then tried by a Japanese naval court in October 1943, for spying and conspiring against Japan. The couple were sentenced to death for high treason on 11 December 1943 and executed nine days later – along with 300 other people – in Banjermasin. Upon finally learning of their fate, the ICRC concluded that the Japanese authorities must have construed the Vischers’ humanitarian work to help prisoners of war as collaboration with the enemy.

In his last letter to his mother, penned in early 1942, Matthäus noted how difficult he and his wife found it to pursue their humanitarian mission in such perilous circumstances. Yet despite the risks, he and Elisabeth did whatever they could to help those within their remit.